Y-chromosomal Aaron

Y-chromosomal Aaron is the name given to the hypothesized most recent common ancestor of the patrilineal Jewish priestly caste known as Kohanim (singular "Kohen", also spelled "Cohen"). According to the traditional understanding of the Hebrew Bible, this ancestor was Aaron, the brother of Moses.

While some early genetic studies were seen as possibly supporting the traditional biblical narrative, this view was subsequently challenged with some researchers arguing that the genetic evidence "refutes the idea of a single founder for Jewish Cohanim who lived in Biblical times."[1][2] However, studies in 2017 and 2021 have provided further support for the model of descent from a common ancestor.[3][4]

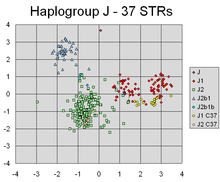

The original scientific research was based on the hypothesis that a majority of present-day Jewish Kohanim share a pattern of values for six Y-STR markers, which researchers named the extended Cohen Modal Haplotype (CMH).[5] Subsequent research using twelve Y-STR markers indicated that nearly half of contemporary Jewish Kohanim shared Y-chromosomal J1 M267 (specifically haplogroup J-P58, also called J1c3), while other Kohanim share a different ancestry, such as haplogroup J2a (J-M410).[6] The latest studies using single nucleotide polymorphic markers have further narrowed the results down to a single sub-branch known as J1-B877 (also known as J1-Z18271).[3][4]

Background

[edit]For human beings, the normal number of chromosomes is 46, of which 23 are inherited from each parent. Two chromosomes, the X and Y, determine sex. Females have two X chromosomes, one inherited from each of their parents. Males have an X chromosome inherited from their mother, and a Y chromosome inherited from their father.

Males who share a common patrilineal ancestor also share a common Y chromosome, diverging only with respect to accumulated mutations. Since Y-chromosomes are passed from father to son, all Kohanim men should theoretically have nearly identical Y chromosomes; this can be assessed with a genealogical DNA test. As the mutation rate on the Y chromosome is relatively constant, scientists can estimate the elapsed time since two men had a common ancestor.

Although Jewish identity has traditionally (according to rabbinic-Jewish law I.E. since around the 1st century CE) been passed by matrilineal descent, membership in the Jewish Kohanim caste has been determined by patrilineal descent (see Presumption of priestly descent). Modern Kohanim are traditionally regarded in Judaism as male descendants of biblical Aaron, a direct patrilineal descendant of Abraham, according to the lineage recorded in the Hebrew Bible (שמות / Sh'mot/Exodus 6).

With the development of methods to follow specific DNA sequences of the human genome, interest in the Cohanim (and Levites) has gained new momentum as an instrument for proof of the common origins of the current Jewish ethnic-groups in the population of the Land of Israel two thousand years ago, as narrated in the biblical story.[7] Skorecki, who carried out the initial study, told the journalist Jon Entine, "I was interested in the question: To what extent was our shared oral tradition matched by other evidence?"[1][8]

Initial study

[edit]The Kohen hypothesis was first tested through DNA analysis in 1997 by Prof. Karl Skorecki and collaborators from Haifa, Israel. In their study, "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests," published in the journal Nature,[9] they found that the Kohanim appeared to share a different probability distribution compared to the rest of the Jewish population for the two Y-chromosome markers they tested (YAP and DYS19). They also found that the probabilities appeared to be shared by both Sephardic and Ashkenazi Kohens, pointing to a common Kohen population origin before the Jewish diaspora at the destruction of the Second Temple. However, this study also indicated that only 48% of Ashkenazi Kohens and 58% of Sephardic Kohens have the J1 Cohen Modal Haplotype. Such genetic markers were also found in approximately 5% of Jews who did not believe themselves to be kohanim.[9]

In a subsequent study the next year (Thomas MG et al., 1998),[5] the team increased the number of Y-STR markers tested to six, as well as testing more SNP markers. Again, they found that a clear difference was observable between the Kohanim population and the general Jewish population, with many of the Kohen STR results clustered around a single pattern they named the Kohen Modal Haplotype:

xDE[9] xDE,PR[5] Hg J[10] CMH.1[5] CMH[5] CMH.1/HgJ CMH/HgJ Ashkenazi Cohanim (AC): 98.5% 96% 87% 69% 45% 79% 52% Sephardic Cohanim (SC): 100% 88% 75% 61% 56% 81% 75% Ashkenazi Jews (AI): 82% 62% 37% 15% 13% 40% 35% Sephardic Jews (SI): 85% 63% 37% 14% 10% 38% 27%

Here, becoming increasingly specific, xDE is the proportion who were not in Haplogroups D or E (from the original paper); xDE,PR is the proportion who were not in haplogroups D, E, P, Q or R; Hg J is the proportion who were in Haplogroup J (from the slightly larger panel studied by Behar et al. (2003)[10]); CMH.1 means "within one marker of the CMH-6"; and CMH is the proportion with a 6/6 match. The final two columns show the conditional proportions for CMH.1 and CMH, given membership of Haplogroup J.

The data show that the Kohanim were more than twice as likely to belong to Haplogroup J than the average non-Cohen Jew. Of those who did belong to Haplogroup J, the Kohanim were more than twice as likely to have an STR pattern close to the CMH-6, suggesting a much more recent common ancestry for most of them compared to an average non-Kohen Jew of Haplogroup J.

Dating

[edit]Thomas, et al. dated the origin of the shared DNA to approximately 3,000 years ago (with variance arising from different generation lengths). The techniques used to find Y-chromosomal Aaron were first popularized in relation to the search for the patrilineal ancestor of all contemporary living humans, Y-chromosomal Adam.

Subsequent calculations under the coalescent model for J1 haplotypes bearing the Cohanim motif gave time estimates that place the origin of this genealogy around 6,200 years ago (95% CI: 4.5–8.6 Kybp), earlier than previously thought, and well before the origin of Judaism (David Kingdom, ~2.0 Kybp).[11]

Responses

[edit]The finding led to excitement in religious circles, with some seeing it as providing some proof of the historical veracity of the priestly covenant or other religious convictions.[12][1][7][13][14]

Following the discovery of the very high prevalence of 6/6 CMH matches amongst Kohanim, other researchers and analysts were quick to look for it. Some groups have taken the presence of this haplotype as indicating possible Jewish ancestry, although the chromosome is not exclusive to Jews. It is widely found among other Semitic peoples of the Middle East.[1]

Early research suggested that the 6/6 matches found among male Lemba of Southern Africa confirmed their oral history of descent from Jews and connection to Jewish culture.[15] Later research has been unable to confirm this (due to the fact that CMH was widely found among other Semitic peoples of the Middle East) although it has shown that some male Lemba have Middle Eastern ancestry.[1][16][17][2]

Critics such as Avshalom Zoossmann-Diskin suggested that the paper's evidence was being overstated in terms of showing Jewish descent among these distant populations.[18][14]

Limitations

[edit]

One source of early confusion was the low resolution of the available tests. The Cohen Modal Haplotype (CMH), while frequent amongst Kohanim, also appeared in the general populations of haplogroups J1 and J2 with no particular link to the Kohen ancestry. These haplogroups occur widely throughout the Middle East and beyond.[19][20][1][2][14] Thus, while many Kohanim have haplotypes close to the CMH, a greater number of such haplotypes worldwide belong to people with no apparent connection to the Jewish priesthood.

Individuals with at least 5/6 matches for the original 6-marker Cohen Modal Haplotype are found across the Middle East, with significant frequencies among various Arab populations, mainly those with the J1 Haplogroup. These have not been "traditionally considered admixed with mainstream Jewish populations" – the frequency of the J1 Haplogroup is the following: Yemen (34.2%), Oman (22.8%), Negev (21.9%), and Iraq (19.2%); and amongst Muslim Kurds (22.1%), Bedouins (21.9%), and Armenians (12.7%).[21]

On the other hand, Jewish populations were found to have a "markedly higher" proportion of full 6/6 matches, according to the same (2005) meta-analysis.[21] This was compared to these non-Jewish populations, where "individuals matching at only 5/6 markers are most commonly observed."[21]

The authors Elkins, et al. warned in their report that "using the current CMH definition to infer relation of individuals or groups to the Cohen or ancient Hebrew populations would produce many false-positive results," and note that "it is possible that the originally defined CMH represents a slight permutation of a more general Middle Eastern type that was established early on in the population prior to the divergence of haplogroup J. Under such conditions, parallel convergence in divergent clades to the same STR haplotype would be possible."[21]

Cadenas et al. analysed Y-DNA patterns from around the Gulf of Oman in more detail in 2007.[22] The detailed data confirm that the main cluster of haplogroup J1 haplotypes from the Yemeni appears to be some genetic distance from the CMH-12 pattern typical of eastern European Ashkenazi Kohanim, but not of Sephardic Kohanim.

Multiple ancestries

[edit]While there is evidence from Josephus and rabbinic sources that this tradition existed [I.E. was practiced and believed] by the end of the Second Temple (1st century CE, nearly a millennium and a half after the tradition places Aaron), there is no further evidence to support its historicity. According to modern biblical scholarship, a historical-critical reading of the biblical text suggests that the origin of the priesthood is much more complex, and that for much if not all of the First Temple period, kohen was not (necessarily) synonymous with "Aaronide". Rather, this traditional identity seems to have been adopted sometime around the second temple period.[23][12][24]

Even within the Jewish Kohen population, it became clear that there were multiple Kohen lineages, including distinctive lineages both in Haplogroup J1 and in haplogroup J2.[25][6][1][12][26] Other groups of Jewish lineages (i.e. Jews who are non-kohanim) and even non-Jews were found in Haplogroup J2 that matched the original 6-marker CMH, but which were unrelated and not associated with Kohanim.[1][2][14] Current estimates, based on the accumulation of SNP mutations, place the defining mutations that distinguish haplogroups J1 and J2 as having occurred about 20 to 30,000 years ago.[1]

Subsequent studies

[edit]Subsequent research (by the original researchers and others) has challenged the original conclusion in a number of ways and has in fact shown that the genealogical record "refutes the idea of a single founder for Jewish Cohanim who lived in Biblical times."[1][2][12][27][3][26][14]

A 2009 academic study by Michael F. Hammer, Doron M. Behar, et al. examined more STR markers in order to sharpen the "resolution" of these Kohanim genetic markers, thus separating both Ashkenazi and other Jewish Kohanim from other populations, and identifying a more sharply defined SNP haplogroup, J1e* (now J1c3, also called J-P58*) for the J1 lineage. The research found "that 46.1% of Kohanim carry Y chromosomes belonging to a single paternal lineage (J-P58*) that likely originated in the Near East well before the dispersal of Jewish groups in the Diaspora. Support for a Near Eastern origin of this lineage comes from its high frequency in our sample of Bedouins, Yemenis (67%), and Jordanians (55%) and its precipitous drop in frequency as one moves away from Saudi Arabia and the Near East (Fig. 4). Moreover, there is a striking contrast between the relatively high frequency of J-58* in Jewish populations (»20%) and Kohanim (»46%) and its vanishingly low frequency in our sample of non-Jewish populations that hosted Jewish diaspora communities outside of the Near East."[6] The authors state, in their "Abstract" to the article:

- "These results support the hypothesis of a common origin of the CMH in the Near East well before the dispersion of the Jewish people into separate communities, and indicate that the majority of contemporary Jewish priests descend from a limited number of paternal lineages."

However, the study did not support a single Y-chromosomal Aaron from the biblical period, rather it showed a "limited number of paternal lineages" from around that period.[12][26] Subsequent analysis found that even the "extended Cohen Modal Haplotype" probably split off from an older Cohen haplotype far more recently, less than 1,500 years ago.[28][14]

Kohanim in other haplogroups

[edit]Behar's 2003 data[10] point to the following Haplogroup distribution for Ashkenazi Kohanim (AC) and Sephardic Kohanim (SC) as a whole:

Hg: E3b G2c H I1b J K2 Q R1a1 R1b Total AC 3 0 1 0 67 2 0 1 2 76 4% 1½% 88% 2½% 1½% 2½% 100% SC 3 1 0 1 52 2 2 3 4 68 4½% 1½% 1½% 76% 3% 3% 4½% 6% 100%

The detailed breakdown by 6-marker haplotype (the paper's Table B, available only online) suggests that at least some of these groups (e.g. E3b, R1b) contain more than one distinct Kohen lineage. It is possible that other lineages may also exist, but were not captured in the sample.

Hammer et al. (2009) identified Cohanim from diverse backgrounds, having in all 21 differing Y-chromosome haplogroups: E-M78, E-M123, G-M285, G-P15, G-M377, H-M69, I-M253, J-P58, J-M172*, J-M410*, J-M67, J-M68, J-M318, J-M12, L-M20, Q-M378, R-M17, R-P25*, R-M269, R-M124 AND T-M70.[6]

Y-chromosomal Levi

[edit]Similar investigation was made of males who identify as Levites. The priestly Kohanim are believed to have descended from Aaron (among those who believe he was a historical figure). He was a descendant of Levi, son of Jacob. The Levites comprised a lower rank of the Temple priests. They are considered descendants of Levi through other lineages. Levites should also therefore in theory share common Y-chromosomal DNA.

However, similar studies into Levite origins found the Levite genome to be significantly less homogeneous. While commonalities were found within the Ashkenazi-Levite genome (R1a-Y2619), no haplotype frequently common to Levites in general [I.E. Ashkenazi & Sephardi] was found.[1][29][7] Additionally, the haplotype that was commonly found in Ashkenazi Levites is of a relatively recent origin from a single common ancestor estimated to have lived around 1.5–2.5 thousand years ago.[1][10][30] Also, when further compared to the most frequent founding lineage found among Ashkenazi Cohen males,[31] it was found that they do not share a common male ancestor within the time frame of the Biblical narrative.[3] Finally, it is unclear whether the origin is Eastern Europe or the greater Middle East region (including Iran);[7] however, the most recent findings indicate the latter.

The 2003 Behar et al. investigation of Levites found high frequencies of multiple distinct markers, suggestive of multiple origins for the majority of non-Aaronid Levite families. One marker, however, present in more than 50% of Eastern European (Ashkenazi) Jewish Levites, points to a common male ancestor or very few male ancestors within the last 2000 years for many Levites of the Ashkenazi community. This common ancestor belonged to the haplogroup R1a1, which is typical of Eastern Europeans or West Asians, rather than the haplogroup J of the Cohen modal haplotype. The authors proposed that the Levite ancestor(s) most likely lived at the time of the Ashkenazi settlement in Eastern Europe, and would thus be considered founders of this line.[10][32][30] further speculating that the ancestor(s) were unlikely to have descended from Levites of the Near East.

However, a Rootsi, Behar, et al. study published online in Nature Communications in December 2013 disputed the previous conclusion. Based on its research into 16 whole R1 sequences, the team determined that a set of 19 unique nucleotide substitutions defines the Ashkenazi R1a lineage. One of these is not found among Eastern Europeans, but the marker was present "in all sampled R1a Ashkenazi Levites, as well as in 33.8% of other R1a Ashkenazi Jewish males, and 5.9% of 303 R1a Near Eastern males, where it shows considerably higher diversity."[33] Rootsi, Behar, et al., concluded that this marker most likely originates in the pre-Diasporic Hebrews in the Middle East. However, they agreed that the data indicates an origin from a single common ancestor.[33]

Samaritan Kohanim

[edit]The Samaritan community in the Middle East survives as a distinct religious and cultural sect. It constitutes the oldest and smallest ethnic minorities in the Middle East, numbering slightly more than 800 members. According to Samaritan accounts, Samaritan Kohanim are descended from Levi, the Tsedaka clan is descended from Manasseh, while the Dinfi clan and the Marhiv clan are descended from Ephraim.[34] Samaritans claim that the southern tribes of the House of Judah left the original worship as set forth by Joshua, and the schism took place in the twelfth century BCE at the time of Eli.[35] The Samaritans have maintained their religion and history to this day, and claim to be the remnant of the House of Israel, specifically of the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh with priests of the line of Aaron/Levi.

Since the Samaritans have maintained extensive and detailed genealogical records for the past 13–15 generations (approximately 400 years) and further back, researchers have constructed accurate pedigrees and specific maternal and paternal lineages. A 2004 Y-Chromosome study concluded that the lay Samaritans belong to haplogroups J1 and J2, while the Samaritan Kohanim belong to haplogroup E-M35.[36]

"The Samaritan M267 lineages differed from the classical Cohen modal haplotype at DYS391, carrying 11 rather than 10 repeats", as well as, have a completely different haplogroup, which should have been "J1". Samaritan Kohanim descend from a different patrilineal family line, having haplogroup E1b1b1a (M78) (formerly E3b1a).[36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l

Ostrer H (2012). Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. Oxford University Press. pp. 97, 96–101. ISBN 978-0-19-537961-7.

This finding generated considerable excitement, because it was taken as evidence of the fidelity of an oral tradition extending over millennia... it has been discovered this Y-chromosomal set of markers is not unique to Jewish men... this record refutes the idea of a single founder for Jewish Cohanim who lived in Biblical times... Y-chromosomal analysis of Levites has demonstrated multiple origins that depend on the Diaspora community from which they came—they are not all the descendants of tribal founder Levi.

Cite error: The named reference "Ostrer2012" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e

Tofanelli S, Taglioli L, Bertoncini S, Francalacci P, Klyosov A, Pagani L (10 November 2014). "Mitochondrial and Y chromosome haplotype motifs as diagnostic markers of Jewish ancestry: a reconsideration". Frontiers in Genetics. 5: 384. doi:10.3389/fgene.2014.00384. PMC 4229899. PMID 25431579.

In conclusion... the overall substantial polyphyletism as well as their systematic occurrence in non-Jewish groups highlights the lack of support for using them either as markers of Jewish ancestry or Biblical tales.

Cite error: The named reference "Tofanelli2014" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d

Behar DM, Saag L, Karmin M, Gover MG, Wexler JD, Sanchez LF, et al. (November 2017). "The genetic variation in the R1a clade among the Ashkenazi Levites' Y chromosome". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 14969. Bibcode:2017NatSR...714969B. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14761-7. PMC 5668307. PMID 29097670.

Remarkably, the five Ashkenazi Cohen samples formed the tight cluster J1b-B877, shared only with one Yemenite, one Bulgarian and one Moroccan Cohen coalescing ~2,570 ybp (Table 1).

- ^ a b

Sahakyan H, Margaryan A, Saag L, Karmin M, Flores R, Haber M, et al. (March 2021). "Origin and diffusion of human Y chromosome haplogroup J1-M267". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 6659. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.6659S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-85883-2. PMC 7987999. PMID 33758277.

Another sub-branch—J1a1a1a1a1a1a2-B877—is specific to the Jewish Cohens [...] Its TMRCA of ~ 3.2 kya (95% HPD = 2.4–4.0 kya) overlaps with the previous estimate.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas MG, Skorecki K, Ben-Ami H, Parfitt T, Bradman N, Goldstein DB (July 1998). "Origins of Old Testament priests". Nature. 394 (6689): 138–40. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..138T. doi:10.1038/28083. PMID 9671297. S2CID 4398155.

- ^ a b c d Hammer MF, Behar DM, Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Hallmark B, Erez T, et al. (November 2009). "Extended Y chromosome haplotypes resolve multiple and unique lineages of the Jewish priesthood". Human Genetics. 126 (5): 707–17. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0727-5. PMC 2771134. PMID 19669163.

- ^ a b c d

Falk R (2017). Zionism and the Biology of Jews. Springer. pp. 186, 183–188. ISBN 978-3-319-57345-8.

interest in the Cohanim (and Levites) has gained new momentum as an instrument for proof of the common origins of the current Jewish ethnic groups in the population of the Land of Israel two thousand years ago, as narrated in the biblical story... These results appear to be a striking confirmation of the oral tradition). However, not all data accorded with these findings... Although no haplotype frequently common to Levites was found, a cluster of haplotypes with a high degree of relatedness was found among the Ashkenazi Levites... According to Kevin Brook.. the Ashkenazi variety of R1a1 comes from the Asian continental branch, the origins of which are believed to be in ancient Iran rather than in the European branch of the Slavic Belarusians Sorbs... Behar and his associates... point out, however, that the Levite cluster of the R-M17 haplotype is very common in non-Jewish populations of North Eastern Europe. It is reasonable to assume that the origin of the Jewish haplotypes is in non-Jewish Europeans, some of whose male progeny acquired the name (and status) of Levites.

- ^ Entine J (2007). Abraham's Children: Race, Identity, and the DNA of the Chosen People. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-40839-4.

- ^ a b c Skorecki K, Selig S, Blazer S, Bradman R, Bradman N, Waburton PJ, et al. (January 1997). "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests". Nature. 385 (6611): 32. Bibcode:1997Natur.385...32S. doi:10.1038/385032a0. PMID 8985243. S2CID 5344425.

- ^ a b c d e Behar DM, Thomas MG, Skorecki K, Hammer MF, Bulygina E, Rosengarten D, et al. (October 2003). "Multiple origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y chromosome evidence for both Near Eastern and European ancestries". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (4): 768–79. doi:10.1086/378506. PMC 1180600. PMID 13680527.

- ^ Tofanelli S, Ferri G, Bulayeva K, Caciagli L, Onofri V, Taglioli L, et al. (November 2009). "J1-M267 Y lineage marks climate-driven pre-historical human displacements". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (11): 1520–4. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.58. PMC 2986692. PMID 19367321.

- ^ a b c d e

Miller YS (2015). Sacred Slaughter: The Discourse of Priestly Violence as Refracted Through the Zeal of Phinehas in the Hebrew Bible and in Jewish Literature (PDF) (PhD). Harvard University. pp. 8–17.

Skorecki's study generated much excitement in the wider Jewish community, as it was seen as vindicating at least one aspect of the historicity of the Hebrew Bible... recent research on the Cohen Modal Haplotype seems to vindicate the historical-critical hypothesis of competing priestly clans

- ^ Weitzman, Steven (2017). "DNA and the Origin of the Jews". TheTorah.com.

the existence of the CMH along with its dating range were suggestive enough to lead the public to mistake the genetic findings as scientific evidence that cohanim were descendant from Aaron himself.

- ^ a b c d e f Weitzman, Steven (2019). The Origin of the Jews: The Quest for Roots in a Rootless Age. Princeton University Press. pp. 297–298, 294. ISBN 978-0-691-19165-2.

Subsequent research has challenged this conclusion in a number of ways. One big problem is that the Cohen Modal Haplotype is found not only in priests but also among non-Jewish populations in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. At first there were efforts to suggest such populations might also be descendant from the Hebrews, as in the famous case of the Lemba, an African tribe in Southern Africa (more about them a bit later). But it has since become clear that the original Cohen Modal Haplotype might have been common among Middle Eastern populations, not exclusive to the Jews or their Israelite ancestors... the extended Cohen Modal Haplotype, the version that is supposed to distinguish Jewish priests, probably split off from an older Cohen haplotype far more recently than earlier geneticists concluded. Beyond the question of when the split occurred, the authors of this study make a larger point: figuring out the right mutation rate to apply is a hotly contested issue; mutation rates are not constant in the real world, and the longer the time span to a common ancestor, the harder it is to pinpoint a distinctive genetic signature or to accurately estimate the amount of time involved.

- ^ Thomas MG, Parfitt T, Weiss DA, Skorecki K, Wilson JF, le Roux M, et al. (February 2000). "Y chromosomes traveling south: the cohen modal haplotype and the origins of the Lemba--the "Black Jews of Southern Africa"". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (2): 674–86. doi:10.1086/302749. PMC 1288118. PMID 10677325.

- ^ Soodyall H, Kromberg JG (29 October 2015). "Human Genetics and Genomics and Sociocultural Beliefs and Practices in South Africa". In Kumar D, Chadwick R (eds.). Genomics and Society: Ethical, Legal, Cultural and Socioeconomic Implications. Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-12-420195-8.

- ^ Soodyall H (October 2013). "Lemba origins revisited: tracing the ancestry of Y chromosomes in South African and Zimbabwean Lemba". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 103 (12 Suppl 1): 1009–13. doi:10.7196/samj.7297 (inactive 10 November 2024). PMID 24300649.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Zoossmann-Diskin, Avshalom (2000). "Are today's Jewish priests descended from the old ones?". Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 51 (2–3): 156–162. (Summary)

- ^ Nebel A, Filon D, Brinkmann B, Majumder PP, Faerman M, Oppenheim A (November 2001). "The Y chromosome pool of Jews as part of the genetic landscape of the Middle East". American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (5): 1095–112. doi:10.1086/324070. PMC 1274378. PMID 11573163.

- ^ Semino O, Magri C, Benuzzi G, Lin AA, Al-Zahery N, Battaglia V, et al. (May 2004). "Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- ^ a b c d Ekins J, Tinah EN, Myres NM, Ritchie KH, Perego UA, Ekins JB, et al. (2005). "An Updated World-Wide Characterization of the Cohen Modal Haplotype" (PDF). ASHG Meeting October 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ Cadenas AM, Zhivotovsky LA, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Underhill PA, Herrera RJ (March 2008). "Y-chromosome diversity characterizes the Gulf of Oman". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16 (3): 374–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201934. PMID 17928816. S2CID 32386262.

- ^ Leuchter M (2019). "How All Kohanim Became "Sons of Aaron" - TheTorah.com". TheTorah.com.

- ^ * "Priests and Priesthood". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 16 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Reference USA. 2007. pp. 514–515, 513–516, 513–526.

the first priests were not necessarily from the levite tribe, though several dynasties of priests did descend from this tribe... in the temples the right to officiate as priests was reserved for specific families which generally traced their lineage to the tribe of Levi.

- Weitzman S (2017). "DNA and the Origin of the Jews - TheTorah.com". TheTorah.com.

We do not know if Aaron actually existed, but there is evidence from Josephus and rabbinic sources that priestly status was transmitted from father to son in the time of the Second Temple and the following centuries.

- Frankel D (2019). "The Flowering Staff: Proof of Aaron's or the Levites' Election?". TheTorah.com.

Originally, however, the story presented YHWH's selection of the tribe of Levi as his priestly caste... According to this verse [Deut 10:8] (see also Deut 18:1-8; 33:8-10), YHWH chose the entire tribe of Levi from all the other tribes to serve as priests before him... Num 17, which presented the Levites, not the Aaronides, as the chosen priests.

- Levine E (2015). "The Historical Circumstances that Inspired the Korah Narrative - TheTorah.com". TheTorah.com.

...the historical process by which the Aaronides became a separate class among the Levites and superior to them... Deuteronomy, for example, does not seem to differentiate priests from Levites... No separate group of kohanim seems to exist, nor is the priesthood associated with Aaron or his descendants in the Deuteronomic corpus.

- Berlin A (2013). "The Levite Rebellion Against The Priesthood: Why Were we demoted? - TheTorah.com". TheTorah.com.

The Korah story reflects part of the history of the growth of the priesthood. Korah's complaint harks back to a recollection that the elevated role of Aaron and his sons was once the role of all Levites.

- Weitzman S (2017). "DNA and the Origin of the Jews - TheTorah.com". TheTorah.com.

- ^ Malaspina P, Tsopanomichalou M, Duman T, Stefan M, Silvestri A, Rinaldi B, et al. (July 2001). "A multistep process for the dispersal of a Y chromosomal lineage in the Mediterranean area". Annals of Human Genetics. 65 (Pt 4): 339–49. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6540339.x. hdl:2108/44448. PMID 11592923. S2CID 221448190.

Confusingly, because only four of the markers that Malaspina et al. tested were markers in common with the CMH study, three of which matched, they originally concluded that all of the CMH matches should be identified with what is now called Haplogroup J2. This is now known not to be the case. - ^ a b c

Relethford, John H.; Bolnick, Deborah A. (2018). Reflections of Our Past: How Human History Is Revealed in Our Genes. Routledge. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-429-89171-7.

In sum, the presence of the J-P58* haplogroup is a marker of Middle Eastern ancestry, and the more specific Extended CMH is a marker of Kohanim ancestry. Of course, many Kohanim have other Y-chromosome haplotypes, so there is not a one-to-one correlation, and there was probably more than one founding male lineage for the Kohanim.

- ^

Elhaik, Eran (2016). "In Search of the jüdische Typus: A Proposed Benchmark to Test the Genetic Basis of Jewishness Challenges Notions of "Jewish Biomarkers"". Frontiers in Genetics. 7: 141. doi:10.3389/fgene.2016.00141. PMC 4974603. PMID 27547215.

This reasoning also characterizes the decade old pursuit of "Cohen" and "Levite", markers. Although dispelled on numerous occasions (Zoossmann-Diskin, 2006; Klyosov, 2009; Tofanelli et al., 2009), the pursuit for priestly biomarkers continued relentlessly to this day

- ^ Klyosov AA (November 2009). "A comment on the paper: Extended Y chromosome haplotypes resolve multiple and unique lineages of the Jewish Priesthood by M.F. Hammer, D.M. Behar, T.M. Karafet, F.L. Mendez, B. Hallmark, T. Erez, L.A. Zhivotovsky, S. Rosset, K. Skorecki, Hum Genet, published online 8 August 2009". Human Genetics. 126 (5): 719–24, author reply 725–6. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0739-1. PMID 19813025.

A common ancestor of all 99 Cohanim lived 1,075 ±130 ybp, and this timing is reproducible for 9-, 12-, 17-, 22- and 67-marker haplotypes. A much higher values of 3,190 ±1,090 and 3,000 ±1,500 ybp were obtained in the cited paper (Hammer et al. 2009) using incorrect methods and incorrect mutation rates. A common ancestor of all the 99 J1e* Cohanim lived around the tenth century AD... An emphasis of the cited paper on the conclusion that an extended CMH on the J1e*-P58* background that …is remarkably absent in non-Jews and having the estimated divergence time of this lineage…3,190 ±1,090 years is incorrect regarding the divergence time. It is more understandable why the lineage originated only 1,075 ±130 years ago is remarkably absent in non-Jews

- ^

Falk R (21 January 2015). "Genetic markers cannot determine Jewish descent". Frontiers in Genetics. 5: 462. doi:10.3389/fgene.2014.00462. PMC 4301023. PMID 25653666.

No haplotype frequently common to Levites was found

- ^ a b Nebel A, Filon D, Faerman M, Soodyall H, Oppenheim A (March 2005). "Y chromosome evidence for a founder effect in Ashkenazi Jews". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (3): 388–91. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201319. PMID 15523495. S2CID 1466556.

- ^ According to the Torah, Aaron was a great-grandson of Levi, so Kohanim and Levites should share a male ancestor within the time frame of the Biblical narrative.

- ^ Behar DM, Garrigan D, Kaplan ME, Mobasher Z, Rosengarten D, Karafet TM, et al. (March 2004). "Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome variation in Ashkenazi Jewish and host non-Jewish European populations" (PDF). Human Genetics. 114 (4): 354–65. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1073-7. PMID 14740294. S2CID 10310338. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ^ a b Siiri Rootsi, Doron M. Behar, et al., "Eastern origin of Ashkenazi Levites", Nature Communications 4, Article number: 2928 (2013) doi:10.1038/ncomms3928, published online 13 December 2013; accessed 4 October 2016

- ^ Brindle JD (8 October 2018). The Samaritans in Historical, Cultural and Linguistic Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110617306.

- ^ Brindle WA (1984). "The Origin and History of the Samaritans".

- ^ a b Shen P, Lavi T, Kivisild T, Chou V, Sengun D, Gefel D, et al. (September 2004). "Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence variation". Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248–60. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. PMID 15300852. S2CID 1571356.